HOW TO MAKE YOUR POLLINATOR GARDEN THRIVE?

Story by Pat Kerr.

Pollinator gardens - stepping stones of pesticide free, pollen and insect housing - are a positive change in Canada... but according to a British study, we need to do more.

Kim Fellows coordinator with Pollination Canada said, "Of our native bees, 70% are ground nesters, while the other 30% are cavity-dwellers, making their homes in stems of perennial native plants and rotted wood, such as raspberry canes. Native bees also need a continuous bloom of food (pollen and nectar) from blooms in early spring to late fall."

The British study suggests our pollinators starve if they only receive pollen from perennials and field flowers. Pollinators need native shrubs and trees to extend the pollen season, providing nesting sites and navigational aids.

"Hedgerows and trees could hold the key to helping UK bees thrive once again," reports Lancaster University, in Britain. "One of the major causes of the reduction of our pollinators is the degradation of suitable habitats. Tree and hedgerow planting could be a more efficient and cost-effective tactic, alongside the planting of wildflowers, than planting wildflowers alone."

Genevieve Rowe, Lead Biologist of the Native Pollinator Initiative with Wildlife Preservation Canada, suggests we can apply this research to Canada. She said, "While the species composition and diversity in each ecoregion of the world will vary, there are a number of similarities between closely related bees across these regions. Bumblebees in Canada and bumblebees in Europe will share a lot of similar life history traits. That said, the research can certainly be applicable here."

One of the reasons the study suggests trees are valuable to pollinators is more than just about a pollen source. Some pollinators use trees as navigational aids.

The topic is complicated and confusing. Rowe continued, "For bees alone - only one group of pollinators - there are over 20,000 species described, with many more awaiting formal descriptions, and there is extreme diversity within the group. Pollinators use different methods to navigate, and trees / hedgerows have been proposed as one of them. But again, this would likely be species-specific, and you have to consider the biology of the pollinator in question: is it large enough to fly above the trees? Does it travel large enough distances that navigation requirements would be there?"

She said, "Meadows / fields will often produce flowers in succession over the course of the season, and these are huge resources for pollinators. Trees are a bit different, because they offer high density resources (pollinators can get more resources with less expenditure of energy) and are usually blooming early in the spring, when summer flowers have not begun to bloom. For example, bumblebees in Ontario rely heavily on blooming willows in the early days of spring. Queen bumblebees wake from hibernation and set out to find a colony, and one of the only resources they have available to them this early in the year are the blooming willow trees. These blooming trees provide important spring resources for pollinators, before the meadows and fields are available to them."

Fellows was asked by a group of Kitchener Ontario gardeners about controlling populations of cucumber beetle, potato beetle and flea beetle in a community garden. Knowing that attracting predators such as braconid wasps, tachinid flies, ladybugs, soldier beetles, lacewings and assassin bugs through the use of plants supports control without pesticides, Fellows designed and helped plant a "fedge": a living fence.

The garden with 100 plots is in a vast suburban field of mowed grass. The 740-foot perimeter of the garden is demarcated by an orange snow fence, and the fedge was created in a four-foot wide swath around the periphery, thus occupying almost 3000 square feet.

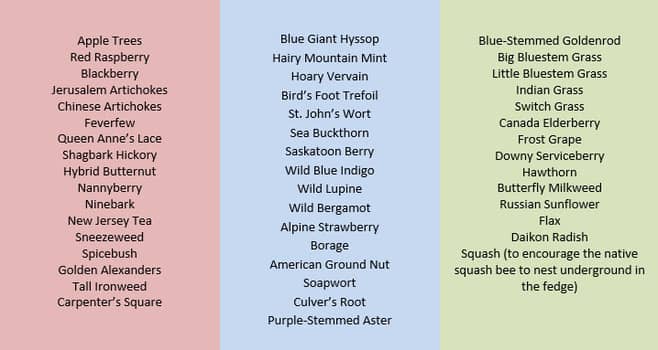

Unlike a vegetable garden that is cleaned each fall (destroying pollinator nesting sites,) the pollinator fedge provides year-round food and habitat for pollinating insects, with the added value of including food plants that humans enjoy. Fellows designed her pollinator fedge to mimic a natural ecosystem on a small scale. The priority is to mix mainly native plants with a variety of heights and woody stems. She included fruit- and nut-bearing trees and shrubs, perennial wildflowers, herbs, grasses, ground covers and vines.

The Lancaster study suggests planting trees in the corners of fields with shrubby plants around and wildflowers transitioning to the field areas. These areas are not to replace pollinator gardens - they are an addition.

WHICH PLANTS WERE INCLUDED IN THE FELLOWS' FEDGE?

Pat Kerr is a freelance writer, who specializes in urban tree care. She received honorary membership in the International Society of Arboriculture in 2011. Her books, "My Tree, My Forest," and her children's book, "We are Planting a Forest," were published this winter.